Introduction

The purpose of this article is to help disability-forward minded individuals and organizations think through the steps of transforming a piece of land they own into an inclusive housing project. This resource details the first five necessary steps to becoming an inclusive houser. Specifically, this piece assumes that you already own the land on which you hope to build. When we refer to “inclusive housing” we mean housing that is built to enable the lived experiences of both people with and without disabilities. This means you can create a community-based setting for the people you already serve while also providing housing to other people in the community who may need affordable or moderately priced housing options. By the end of this article, you will know and better understand the tasks to undertake to get started in turning a piece of land into inclusive housing.

If you would like information on necessary steps with no land ownership, stay tuned for our next installment entitled “How to Choose A Development Partner.”

Step #1: Feasibility

Task: Evaluate what you can feasibly build

Local zoning codes dictate where housing can go in each municipality. You can usually find out the allowable uses from your local planning department. For instance, in San Francisco, California this information is found on the local planning website. Types of allowable uses include:

- Residential: Housing can be built here

- Commercial/Industrial: No housing can be built without additional approval from the local municipality which sometimes can be done but requires legal costs and extra development time

- Mixed Use: Housing is generally encouraged on top of commercial uses (like a retail store on the bottom floor and housing on top)

The local zoning code will also determine the height and density limits for your housing development. If you are looking to build inclusive, accessible, multi-family housing, the best two choices are:

- An apartment building with at least 4 stories: These projects are better in town and city centers where land is more expensive. Elevators are expensive, and if you have at least 4 stories, it makes having an elevator more cost effective. These would be best in an area that is zoned to allow buildings at least 40 feet high, with a density allowance of at least 20 units per acre, and a floor-to-area ratio requirement of no less than 1.

- One-story cluster housing (or cottage communities): These communities are better for when you have more land and the zoning rules limit building height to less than 20 feet, with a density allowance of fewer than 15 units per acre, and a floor to area ratio requirement of less than 1.

Step #2: Financeability

Task: Determine whether the building you would like to build can be financed

The baseline of many housing projects is a “proforma” – a financial model that estimates both the costs to build a project (uses) and where you would get the money to build the project (sources). There are many great resources available to help you learn and understand, at a high level, what it takes to build a project financially, like the Urban Institute’s interactive affordable housing calculator and the Terner’s Center Making it Pencil paper.

Once you understand the fundamentals behind financing your ideal housing project, reach out to a housing finance consultant that can help you put together a model.

Step #3: Vision + Priorities

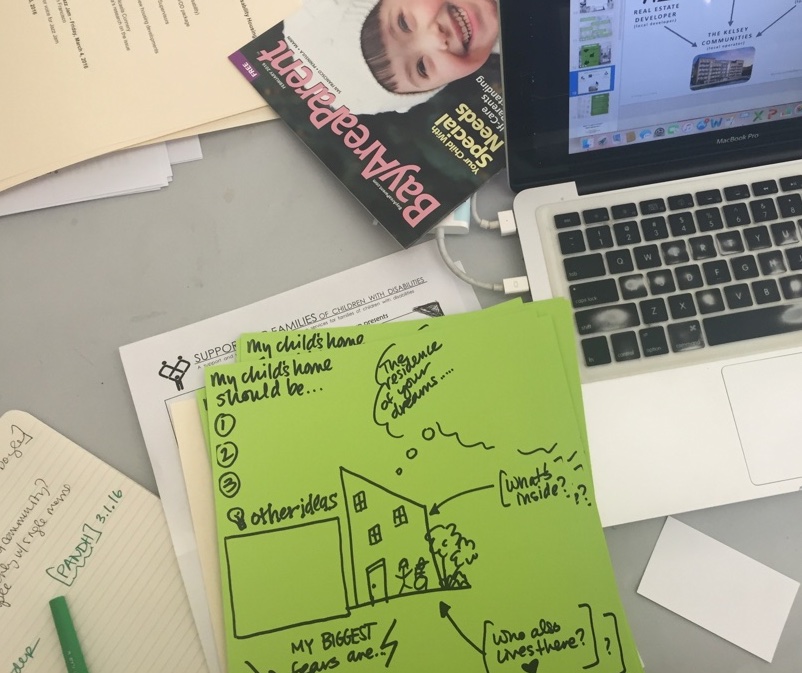

Task: Outline what is most important to your organization and the community

Before bringing in external partners, it is incredibly important to identify and prioritize the most important aspects of the housing project you would like to build. In projects The Kelsey has built we call these the “Guiding Principles.” Aligning both internally, with your team, and externally, with the community where the project will be is important prior to bringing in a development partner.

As an example, early on in the process of organizing The Kelsey Civic Center (TKCC) in downtown San Francisco, we realized this project had to accomplish a lot! We had won the site through the Reinventing Cities C40 competition, so we knew our project would need to responsively address ambitious climate-conscious goals. We conceptualized TKCC as a beacon of disability justice, in alignment with The Kelsey’s mission of building homes for people with disabilities and with our project location just down the street from the historic and transformational 504 sit-ins. And, we needed to address the housing needs of San Francisco, the epicenter of the affordable housing crisis. With those key components in mind, we assembled our project vision within the following parameters, and communicated these parameters while onboarding each partner so every team member knew exactly how tradeoffs should be made:

- Affordable and Feasible: Total development cost of less than [target cost] per unit to build safe and affordable housing for low and moderate income San Franciscians.

- Inclusive and Interdependent Community: Universally designed building with 25% of units reserved to serve households with an adult member with a disability who utilizes supportive services; racially and culturally diverse community with mutually supportive environment rooted in the ethos of interdependence and informal support networks.

- Resilient and Sustainable Design: Meets C40 requirements of being as carbon-neutral as possible, with an all electric building, and Green Point Rated (GPR) certified.

- An Asset to the Neighborhood: Offers programming that is inclusive and welcoming of neighbor residents by providing a café or community accessible shared spaces such as Community Open Space.

- Accelerated: Aspires to move in residents by 2024.

- Replicable: Assembles a financing package including state, local, and private funding sources that is able to be reproduced or analogized to in other projects by other developers within and outside of the state. Employs Universal Design standards and a disability-forward tenant services model and actively shares these approaches with the development community.

These priorities may not be as detailed as TKCC’s from the outset of putting together your project, but it is worth being proactive in aligning with the most important stakeholders within your organization in identifying the “must-have” aspects versus the “nice to have” aspects.

One way to know what principles to prioritize for the community is to facilitate a Together We Can Do More Initiative. Prior to building TKCC, The Kelsey led an organizing process that focused on identifying funding and funding gaps, strategies, and operating models to address the housing needs of adults with disabilities around the Bay Area. Cross-sector stakeholders participated in a three-part workshop series that defined problems driving disability housing shortages, sourced interventions, and designed what new solutions could and should look like in the Bay Area and beyond. This process is one that can be implemented in your own community.

Step #4: Sourcing Partners

Task: Find a development and design partner

Your development partner will be an organization or individual who you select to help you execute the project and bring your vision to life. Developers understand the entire process of building housing from getting local approvals to construction to renting or selling the units; they also help identify potential areas of risk for all partners involved. For example, The Kelsey’s partner for Civic Center is Mercy Housing California, a California-based nonprofit housing development organization with the mission of creating and strengthening healthy communities.

When choosing a development partner, it’s important to research and interview the partner, to make sure they are an appropriate fit for what you are trying to accomplish in your housing community. Your development partner will need to have the technical expertise to help you obtain and efficiently and appropriately utilize the financing package you put together with the feasibility consultant, navigate necessary relationships with government agencies and officials, comply with legal requirements, and work together with other partners like design and construction teams to build the project. The development partner should be a team player who is open-minded and enthusiastic about the priorities and parameters of your disability-forward vision, which you will explain to them, and which you and they will advocate to your other partners in building the project. For an example of the type of experience and portfolio to look for in a partner, Mercy has created and preserved affordable housing for Californians for over 35 years, and owns and manages 151 communities with over 10,300 homes statewide for more than 19,600 people.

Developers work closely with design teams to ensure the building is designed to expectations and local building codes. Your design team should include architecture, planning, and design expertise. The companies and studios you work with should have some experience designing different types of housing for different populations. They should also be an organization that is willing to help implement your disability-forward vision, work within the boundaries of your financing and incorporate legally required design elements that meet the needs of your community as well as the local government.

When onboarding your development partner and design team, a good place to start is to look at The Kelsey’s Inclusive Design Standards, which we worked to create in partnership with Erick Mikiten of Mikiten Architecture. These standards define a set of multifamily housing design and operations strategies. These were co-created by advocates, developers, and architects. The design standard elements support cross-disability accessibility and link disability-forward design choices to intersectional benefits around affordability, sustainability, racial equity, and safety. These standards are a great template, and you and your design and development team can use them to plan and design your project. You should also be sure to engage with your community in this process, as well as incorporating viewpoints of people with disabilities. This important step can identify aspects beyond the design standards that community members would like to see in the project.

Step #5: Designating Roles

Task: Allocate organizational resources to stay engaged in the project

Putting together an affordable, accessible, inclusive and disability-forward housing project isn’t a static activity – there are many unexpected things that can come up along the way. It is important for you, as the owner, organizer, and leader of the project, to stay engaged at each stage of the process. You will work with the different teams you’ve brought into the project to make sure your vision is executed well and the project is built successfully.

Community Engagement During the Entitlement Phase

The entitlement process is the necessary approval process developers must go through to have their projects approved to start construction. The basic process is that developers submit their plans for the project to the city (usually to the Department of Planning), and officials within the department review the plans to make sure they meet objective criteria like building codes and zoning, environmental, and use permit requirements. If they do, then the project is approved for construction.

The risk with entitlements is that the project might not receive approval, or that approvals take a long time and result in a project time delay. In development-friendly settings, the entitlement process will only take a few days or weeks, but in some places, especially for larger projects, this process can be much more time-consuming. If entitlements take a long time, or if the community is against the project and vocalizes opposition at the public entitlement hearings, the cost of development goes up. You, as the project owner and leader, can work to make sure entitlements go smoothly by starting to engage with the local community and government early on in the process, and asking these different groups about their concerns or what they would like to see added to or removed from the project.

Supporting Fundraising if needed During Financing Phase

By the time you select your development partners and start thinking about entitlements and construction, your proforma financial approach to the project will be settled with the financial consultant. The financial outline will clearly define sources of funding you need and pull together in order to make the project work. However, you should think of the proforma as your basic guideline and a living document that you can adjust, if needed, as the project progresses. The Kelsey Ayer Station (TKAS), for instance, has pursued a combination of public financing with tax-exempt tax credits and bonds, concessionary (below market) loans, and private financing from large and individual donors, in order to make the project a reality. Having a variety of funding sources, if possible, works to your advantage, because it means you won’t be dependent on just one source. It’s also important to stay in regular touch with your development and design partners as development takes place to gauge any funding gaps that need addressing.

Sometimes, outside forces can delay a project and require readjustment, for example, Covid-19 caused a supply chain disruption that made the prices of construction materials go up. As the project leader, you will need to work with your team to predict and respond to any issues as they arise, and put together a plan to fundraise or source additional funding for the project. This can be done at the community level, by working with like-minded groups and other stakeholders to host fundraising activities, or at the institutional level, by researching and applying for alternative sources of funding.

Making Sure the Project Stays True to Initial Goals During the Design Phase

Similar to financing, you will also have your design plan set out at the beginning of the project. It will be important to stay in touch with the design team to act as support and inform the decision-making process as the project moves ahead. Establishing a model and cadence of communication with your design team and designating roles early in the process will help to ensure the project moves ahead smoothly and incorporates all the desired disability-forward elements and parameters you prioritized in your conceptualization process.

Helping Avoid Unnecessary Risks During Construction

Developing any sort of real estate project involves an element of risk, because taking a project from concept to completion involves many steps, third parties, government agencies and regulators to deliver different aspects of the project. Mistakes or miscommunications during the construction lifecycle can add to costs, slow down delivery times, and increase the likelihood of construction claims and regulatory violations. One way to minimize these risks is by having a thoughtful plan for construction management and documentation. You can have your development partner manage the project directly, or you can hire a general contractor to be in this role.

If you choose the first path, you’ll enter into several contracts with different sub-contractors who will report to you as they complete their various tasks. The developer would be responsible for managing all of the details of these relationships and have the final say on all the work that goes on in the project. If you choose the second path, which is usually more advantageous for larger projects, the general contractor you hire will be the one overseeing the project, sub-contracting out to different vendors, and overseeing the details of these relationships and ensuring quality of performance. Whatever path you choose, it is important to select partners you trust and are enthusiastic about working on your vision.

Closing

With these helpful steps and guidelines in mind, you will be equipped to start your housing development journey, assemble a strong team of partners and advisors, and put together a strategic plan for transforming your affordable, accessible and inclusive housing idea into a reality. The Kelsey’s Learn Center is updated regularly with additional tips, templates and best practices, so feel free to check it out for more information. And, if you’d like to hear more about our work, want to make an appointment for a consultation or have specific questions, feel free to reach out to our team at hello@thekelsey.org.