Our CEO and co-founder Micaela joined Stephen Beard for his podcast ‘Accessible Housing Matters’ where she shared more on The Kelsey and our approach, vision for impact, and Housing Design Standards for Accessibility and Inclusion. Listen to the full episode on Apple or Spotify.

Full Transcript

Welcome to accessible housing matters. I’m your host, Stephen Beard. I’m a real estate agent and an accessibility specialist. I got into real estate to being the agent for people with disabilities and their families. Through my work, I’ve met 1000s of people. And now I want to share what I’ve learned. Each week, my guests and I will talk about accessibility and housing. Over time, I’ll explore many different aspects of the subject from a wide range of perspectives. Together, we’ll learn about some pretty cool stuff, and inspire you to new ideas, discussions and actions that will really make a difference. Because accessible housing matters. Hello, everyone. Today I’m delighted to welcome Michaela Connery to the podcast. Michaela is the co founder and CEO of the Kelsey. And this is an amazing housing organization based in San Francisco, where she lives. And I’ve invited Michaela on the show today to tell us all about what the Kelsey is, and to explore this really innovative and interesting model for accessible housing. Welcome, mckaela.

01:19

Thanks, Steven. Thanks for having me excited to be here and chat about our our aligned passion for access and inclusion.

01:26

Thank you for saying that. I absolutely feel that very strongly. So let’s start off right with what this is all about. What is the Kelsey? Yeah,

01:34

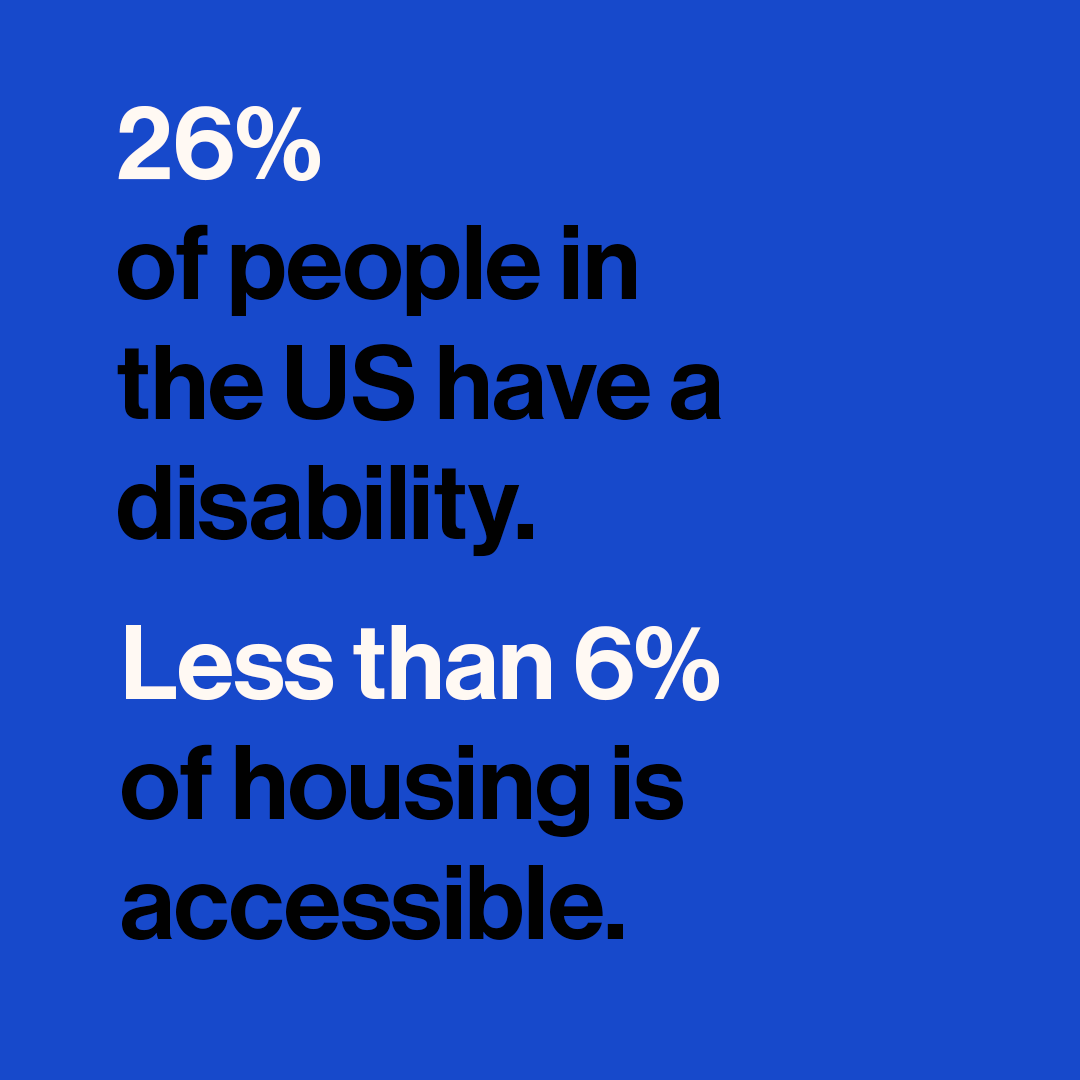

so the Kelsey is a not for profit. And our mission is to advance disability forward housing solutions that open doors to homes and opportunities for everyone. And I think that two part thing of disability forward and opportunities for everyone really is fundamental to what we do. We center on the perspective of and are co led by people with without disabilities, really looking at the critical and unmet and we can go into what some of the critical and unmet housing needs are of people with disabilities in our communities, here in the Bay Area, and nationwide and internationally. So focusing on that critical and unmet housing need of people with disabilities to be accessible, affordable and inclusive. But in doing so we really adopt this concept that doing so just creates better opportunities, better communities, better housing outcomes, better residential experiences. For everyone, it is a classic sort of curb cut effect. centering on disability access, and inclusion is really just centering on a better housing experience and a better community experience for everyone. So that universal benefit. And we have a two part mission, we both develop housing. So we have over 200 homes in our pipeline of accessible inclusive mixed income housing. And then as we develop these housing communities, we do so with the belief that we also have to address the policy funding systems and field leadership so that communities like the Kelsey can someday become the norm. And so we really have this dual part mission of build communities and change systems. You know, there are 61 million people with disabilities in the country, 5 million of them who use some type of or who would be eligible to be received some type of Medicaid funded supportive service. So this is a huge population. And we don’t want to just build community by community. We also as we build those communities want to address the underlying issues and then change the system as we go.

03:29

So I understand the Kelsey has only been in existence since 2017. But yet you’ve been you’ve created over 200 units of housing accessible and affordable housing in that time, that’s really remarkable. And I just want to share with my listeners on a couple of other episodes, I’ve had the opportunity to, to speak with other housing developers of accessible housing. And it’s remarkable how long it took for them to develop their projects, and how much they had to collaborate with lots of different family interests. Many of these organizations are driven by families looking for housing for their parents, or sorry for their, for their disabled children. And so it seems to me from my research that the calcium has come into existence in a very different way with a different modality. Could you talk a little bit about that?

04:19

You are, you know, absolutely correct. When I started this work at Kelsey and even prior to that, I actually started this work myself as a family member of somebody with disabilities. My cousin Kelsey was born with multiple significant disabilities. She and I were three months apart, we really went through every life milestone together. So I did really come to this work from a personal family level of seeing her unmet housing need, and then what do we as a family do to meet that, and immediately, then it became obvious that obviously her need was not unique to Kelsey and that this issue was so much larger. And as a research fellow at Harvard when I was between my first and second year as a public policy student, I went out and travel And visited different disability housing communities across the country and saw exactly what you saw, which is the requirement. And the effort to build housing for people with disabilities was being predominantly lifted by parents. And these parents have done remarkable pioneering work in the name of the housing, yeah, in the name of the housing needs of their children. Yet, that also comes with a really challenged industry in some ways. First of all, I think parents build housing communities for their children and go through these incredible feats to do so. And then once their children are housed, how could we possibly expect them to even parents who have done amazing systems work? How could we expect them to go forward and repeat that model to make it more universally available to everybody and replicate what they do? The second is that you know, what happens to individuals and groups of individuals who don’t have parent advocates, or whose parents you know, are themselves dealing with housing affordability crises, or other, you know, economic insecurity or lack of opportunity that they couldn’t even even if they do have a parent advocate, that parent advocate doesn’t have the access to the resources and time to develop housing to meet their needs. So the equity issues that a parent driven model potentially, you know, creates and really creates a two tiered housing opportunity system. And the third, that’s perhaps the most complex thing to think about is that, you know, we might also default to parent driven models being inherently less, you know, integrated in some level, because parents do often build housing with the idea of protecting their children. And they’re actually not having leaders with disabilities involved in building that housing, to talk about their own lived experience, and what they see as opportunity and need and housing. And so defaulting to parent driven models could not always, but could, you know, lead us to less inclusive, less disability driven housing models and more what parents want for the housing versus what, what children, their children, or what other people with disabilities would want. And so, you know, that’s all to, you know, lift up and acknowledge and celebrate the role that parents have played in pioneering this this field forward. But in the same vein, to say that that cannot be the only leadership in what we do. And in fact, the most important leadership and housing is by people with lived experience with disability themselves. And I say that as a person who doesn’t currently live with a disability, but that it was also really fundamental for me when I started this work, to begin with, that we be co led by people with without disabilities. And it’s something we work on every day, on an org level and on a field across the disability housing field level of making sure that this work is not, you know, by people without disabilities, for people with disabilities, and all the inherent gaps that that would create an embedded, you know, inequity, that that that builds in, but actually, to be co LED. And that’s a, you know, an ongoing effort. And work that we do,

08:01

how involved have people with lived experience been in choosing the developments you’ve decided to build and make contributing to their design and implementation?

08:11

The short answer is, yes, people with disabilities have been involved at like every level, beginning, middle and end and still constantly, you know, evolve and shape and adapt our views. And also note where we have work to do with the qlc, you know, to do ourselves at the qlc to evolve over time. And so some of the ways that people with disabilities have shaped our work is first when we first is when I went out and did research I actually like went and like sat in and like, in some cases slept overnight in where I was able to in housing communities that were targeted to people with disabilities, and really talk to the people that live there themselves, and asked about, you know, what do they like about where they live? What, in addition, talking to the development teams, and the policy teams that were building these projects, actually sat down and tried to understand from people directly what what worked and what didn’t, and what they loved and what they would like different in their housing. So that was like phase one. The second step you we did an organizing and pre development process in the Bay Area leading up to our housing development work in both San Francisco and San Jose, that we have underway now. And that was a process of a nine month, you know, with three different teams, Silicon Valley, San Francisco, and East Bay coming together and putting, you know, a planning around defining the need for housing and disability, identifying the possible interventions and then designing they’re like ideal community models. And those teams included people with disabilities and we did aligned focus groups with them to or you know, had, like, you know, design workshops where people couldn’t write down what they wanted out of their housing and even with like, Velcro picture options so that people who use you know, different communication styles could kind of share their their housing preferences in different ways and the reality Is that people with disabilities have diverse housing preferences? Yeah, exactly. So some people prefer a single family home, some people promote the multifamily. Some people prefer like central urban, some people prefer, you know, roommates versus a studio. So I first of all, I don’t think that even if you do all these interviews, one thing you’ll learn is like, people like different things. And so you’re not going to design for everybody. So ultimately, the Kelsey is choice around both like specific sites, and are then design features was based on a, you know, a group of groups have feedback where there were some key features, definitely access to nearby amenities is a key thing that came up. And so that can be achieved in a lot of ways. But for us, it was really looking at transit oriented sites, and like, you know, centrally located sites. The other thing that came up was kind of flow, which was really interesting that like, that people sort of talked about an extreme of like, super community focused places where people felt like they had to be like, around people all the time, or like, super isolating, I was in a single apartment, and I knew nobody in my building, and I had no community around me like, the reality is that people want that option to have days when they sit in their studio apartment, and don’t talk to anybody, and options where they have a community space to go to and be super active, but not required to go to that community space every day. Because some days you don’t want to talk to anybody. And so that idea of like flow from the private to the share to the public space, came up in a lot of our workshops of how do we design spaces that honor all three of those parts of life. Another thing that came up is access to green space and outdoor amenities. And so while we were really focused on urban development, urban multifamily, that’s definitely our focus at the qlc. Not necessarily because that’s what people with disabilities want more, although we have found one of the research areas is like an increase rural zation of disability that people are pushed out of city centers. And there’s like, super interesting history of that like, from both the kind of the send them to the farm, sort of like institutional history of them being out of sight, out of mind. And then more recently, affordability, which is people being pushed out of city center. So we had the Kelsey have for a couple of different reasons focused on, you know, urban or dense suburban development opportunities, but balanced that with access to outdoor amenities and green spaces, because that that has come come up a lot. And I could go on and on about all these things.

12:25

Definitely fascinating. But I actually want to back up a little bit and this get into some nuts and bolts, if you don’t mind. And then maybe we can go back in to the detail. First, you mentioned there are two projects going on right now tell me a little bit just briefly about each project and when you expect to be having units available for, you know, for and is it a lease or an ownership model and all that stuff? And then after that, I’d like to understand I think my listeners would like to understand the affordability piece.

12:54

Yeah, yeah. So just on the the project San Jose as 115 homes. 25% are explicitly reserved for people with disabilities. Who are you supportive services are at risk of institutionalization, or otherwise defined as a subgroup of people with disabilities. And that community will start construction in the first part of next year, we have been, we’re in the queue for tax credits, we’re construction ready, but we could have a whole podcast about tax credit funding. So that project should start construction in the first part of next year, and then come online in early 2024, late 2023, early 2024. And then we have a project that’s about a year behind that, maybe a little less behind it as things are moving at a clip, which is great, especially if we solve for some of these technical issues that can move this project forward faster. And that’s the Kelsey Civic Center in San Francisco, that’s 112 units, again, 25% reserved. And that project should start at the end of 2022. And open you know about about two years after that. We also have a model that we call our inclusive partner properties, which will be marketing out to others. So if developers are interested in being an inclusive partner property, and that’s really either affordable or market rate homes where people are interested in supporting those to be targeted to people with disabilities, the buildings, we the calci, unlike our other developments had nothing to do with the financing or design and are not you know, in the ownership. But we come in target units to this population and layer on our inclusion concierge programming and support those residents to live in that community. So we have a small pilot, just a couple residents in Oakland that we started and we’ll be continuing to add units into that alongside our developments.

14:39

So these units that you’re building that’s focused on the San Jose and San Francisco ones, is it like an apartment building that you’re going to be renting out unit so it’s not meant for ownership in that model right

14:50

now, although that’s an area that we’ve identified as we think of our next sites and next markets that ownership is for sure something that has come up as a really related to your own. question of what? What are some of the things that people with disabilities have sort of come strong and like their their needs and desires? And how do we meet those and then we haven’t done them all yet. ownership is a is a big one that that has come up before. So I think that that would be cool to explore. But no, these are rental multifamily rental models. And they are, you know, to answer your your second question around affordability, around affordability and segue into that, the homes so our buildings are mixed income by design. So they include both extremely low income affordable homes, homes that are affordable to people who rely on SSI for income, so you know, making $974 a month in California. So either residents have deeply affordable priced home or some of our units actually also have project based vouchers tied to them. For again, people at that Li extremely low income level. And that’s really where the bulk of our reserved homes for people with disabilities are targeted. So we’re talking about affordability, where people are paying between three and $500 a month in rent. So, so really, deeply, deeply affordable. And that’s really key because, you know, it’s funny, there are some housing communities that cost like, you know, $4,000 a month to live. So then people say, well, then 1500 is affordable, like that’s affordable compared to that. But we really focus on making sure that we have, you know, a lot in our case, a large percentage of units, but we would always want to have some percentage of units that are truly affordable to people for whom SSI is their sole source of income, which we found to be a really huge gap and to be the case for you know, so many people with disabilities, you know, we’ve got all sorts of conditions to address SSI should be higher job opportunity should be greater. But the reality is where this is where our country is right now, on the income that people with disabilities have access to, it puts them in that category. The rest of the homes are a mixed income affordability, including some, you know, 60%, ami, up to 60%, median income up to 80%, median income. Those units are not reserved for people with disabilities. And in fact, we by design are working to not be a disability specific community but to be an integrated community. But I will say that, that we look at the reality that while people to those 25% of our residents will come through a reserve disability lottery that are explicitly set aside and reserved. We imagine that of our other 75% of residents that aren’t reserved that there might be you know, the, you know, paraprofessional who works in San Francisco Public Schools who has a physical disability and was attracted to the accessibility of the community and came through the affordable homes but but didn’t come through as an explicit explicit reserved for disability resident or people with invisible disabilities or other types of disabilities who are attracted to this community and who choose to come through in the other mixed income homes because of its inclusivity, even though they didn’t come through the the targeted reserved disability units.

17:53

So will the units that are not set asides and lottery based the ones that are going to be 60 to 80%? ami? Are those ones accessible?

18:04

Yeah. So we have at, you know, we actually this week are publishing our housing design standards for accessibility and inclusion. So the short answer to your question is, yes, they’re all accessible and or adaptable. They’re certain features, and we worked as much as possible. And this was like, I would put this on the board as things we tried to do and didn’t do. But we’d like to do in the future. Like one of the things is, we first started to say we want every single unit in this building to be exactly the same. And we kind of started with like a universal design perspective of like, we want every single unit to be exactly the same. Because one, like, it’s just gonna be better design. And two, it’s better with turnover. So you don’t have to have certain units reserved for different people, when they come out, if somebody doesn’t have their same access needs, you have to change it and figure all that, you know, unit layout out. And it just made for, you know, meeting our goals that when residents come in, they won’t have to change anything about their unit, it’ll just be accessible. And what we learn really quickly is like certain things like a roll in shower, like we were going to do rolling showers in the whole building. And we were like, you know, that isn’t certain people first of all, want a bathtub and not a shower, for access needs are for personal preference needs enrolled showers have waterproofing issues that could actually make a hazard for other people. So there were all these different pieces. So there are some units that have a few different design features. They’re not all exactly the same. But they all have, you know, a pretty, you know, adaptable, accessible and kind of like a baseline of accessibility.

19:32

And you know, when it gets to a point that I’m constantly telling real estate agents when I teach them about accessible real estate, and that is that no two people who have disabilities or I self identify as disabled have the same needs and housing everyone’s needs are unique, regardless of whether they self identify as quote unquote, disabled or not. Right. And I think that that sounds similar to your experience with these roll in showers. I don’t want to forget to ask you about the money. How did he Finance. This is the you know, one of the biggest challenges I we live in here in the Bay Area, one of the most expensive housing markets, if not the most expensive housing market in the country. And to be able to say you’ve got to multi unit projects going on that are going to provide up to over 200 units of housing, at at these discounted rents, raises questions for me about how you were able to get all these partners and create this nonprofit and get this going. And I’m just wondering what the secret sauce is to develop this.

20:36

Yeah. So you know, we right now have a real estate portfolio with our development partners, that’s probably valued at around $150 million, ultimately, will be the customer to developments. And so yes, it takes a lot of money. So a couple things is one how it’s impossible is, you know, I really see money coming in at three phases. And you can’t do it without you got it, you need all three of them, which is you need, you know, front end and back end, seed and gap philanthropic capital, you need seed philanthropic capital to launch these things off the ground when they’re super unknown and super risky, you, you have generous donor partners who understand the need and who are willing to take the front end risk to get it off the ground. And then bring something to life that is deeply needed for both people with and without disabilities, but especially for people with disabilities, launch this with donations that support both our organization but also seed for these projects to acquire sites before you have any of the public funding lined up and all of that. So philanthropic capital is like step one. And we’ve been fortunate to have generous partners, who we work hard to cultivate and bring into and convince of the need around this work. Then phase two is recyclable concessionary lending, you know, housing is is a is a debt and equity game. And so your your some of your philanthropic capital is is an equity, it’s a it’s your your gifts that you have as an organization to put into these projects. But you do need lending that needs to move through these projects. We were fortunate to secure a pre development loan with Google’s affordable housing fund, we were the first investment out of that fund, and also really proud to say that in becoming the first investment out of that fund or loan out of that fund, not only did we get the Kelsey airstation funded but proud to, you know, have brought the Google’s affordable housing team through this process of understanding disability access and inclusion so that they looked at other projects through the lens of not just its affordability, but also its access and inclusion goals. So philanthropic seed money, recyclable ideally concessionary, which is the case with our Google so you know, and when it when it’s concessionary? Well, it’s concessionary in its private money, and it’s getting some interest, and it’s going to be paid back at some point. But it’s taking a little bit more risk than maybe a traditional loan would do, it’s taking a lower interest rate than alone would do. And that’s private. And that kind of gets you through both free development. And in some cases, through construction, we could use lending. And then you got to line up all of that with the public subsidy. And I really one of the things to go back to this research side is, I feel like we were creating a two tiered system where they were like what, you know, fundraising for one off projects are leveraging no public dollars, and they were, you know, a single project that was costing $10 million to serve, you know, a certain number of people and you raised 10 million, you built 10 million worth of housing, we really think that you need a philanthropic role on these projects. And we have about, you know, between three and 7% of our total capital stack is philanthropic of our total project cost is is purely donations, but that those donations are leveraged to then unlock tax credits, a permanent mortgage, city funding county funding state funding federal vouchers, and so we use philanthropy take start the projects off, we recycle lending through the pre development and and construction phase. And then we unlock, you know, predominantly, or projects are mostly publicly subsidized. And we hope someday we’ll have the policy that they’ll be fully publicly subsidized if we change that. And then but they’re not yet because we don’t really have explicit funding out there for either extremely low income, inclusive housing that accessible to people with disabilities. So we do then close the final gap with another set of philanthropic money that final, you know, three to 7% of the total project costs, its donors, again, that come in to get the projects across the finish line, once all these other public sources have been lined up. So their donation has incredible leverage to not just if you you know, you donate, you know, $500,000, you’re actually creating, you know, 10x in real value. So we tie all those. I don’t know if that that’s long answer your question, but we pull all those pieces together.

24:40

Wonderful. Before we wind down our conversation, I wanted to make sure I touched on the advocacy work. Tell me a little bit about the advocacy work that you’re doing.

24:50

Yeah. So like we talked about our mission is to change the systems and policies so that this becomes the norm. And so our advocacy work takes kind of three Different forms, we still do some local and state advocacy that is like, really supporting the conditions that directly benefit the projects that like we are doing. So like we’re like running into barriers in, you know, in our local localities or in the state that like, you know, other affordable housing is working on. And we’re joining that advocacy or other disabilities working on are joining that advocacy to like, fix just real problems and policies or advocate for money like today. That that is that is slightly more like lobbying, transactional advocacy in some ways of like, you know, pushing forward sort of opportunistic policies that are needed to make these projects possible in the next three years. The second type of advocacy we do is really more field building than advocacy, which is noting the gaps in our sector, and pushing those changes through both sharing best practices and our learned center, open sourcing what we do in that learning center, as well as in office hours and through sometimes technical assistance partnerships, and raising up additional leadership in this field among leaders with disabilities. So we had our raise the roof program, that we ran a 12 module training program for leaders with disabilities around housing issues, both to bolster leadership in the field, but also with the hope that that would then you know, it would be a lot better than the Kelsey having to like, show up to, you know, Housing California and represent like the issues around housing and disability than if there was actually a disabled person working as the director of advocacy at Housing California, and they were bringing these issues forward. And it was just embedded into all of this other work. And so by, you know, increasing disabled leadership in the field, that’s not gonna be the end all be all solution. But it’s a really important step in, in diffusing disability access and inclusion across all housing, advocacy, and all housing development. And then the third that I’m really excited about his federal advocacy, we have a committee campaign, sorry, I’m in a program and incubator out of DC called rise justice, where the Kelsey team, along with advocates from across the country are working on a federal policy agenda of what would a disability forward housing package look like? And what could How could that be implemented over the next, you know, three to five years of what would it look like to actually have policy at a federal level through both HUD and HHS, that supports inclusive housing future that that we have the policy mandate very clearly and plainly for on a federal level, we’ve had that policy mandate since the 90s. And that right is really there. But the policy has not been been supportive to make that right. a reality. And so doing doing a lot of work on that. Now,

27:33

that sounds very exciting. Where do you see the qlc? in five years? How much housing how much advocacy? What is it? What’s your dream?

27:43

Yeah, so I think in five years, we would like to have at least five grand up Kelsey communities in different markets across the country. So so not just here in California, but to show that this is possible in different housing markets. And I think more importantly, in five years, we will I often, you know, would refer to what we do as like the three parts that we want to have possible in five years, the the policies, the playbook and the pot of money, that in five years there, we will have a federal policy when that actually the market will now have a you know, a policy platform both through, you know, financing and supportive services, that it’s actually easy to do these kind of communities because the policy support it and the funding is there, there is the the playbook will have done this five times in five maybe different ways, too. So we’ll have a real playbook coupled with our design standards of how do you finance, design and operate these buildings that not only the Kelsey can use, but anybody could use and bring that out. And then we’d have the pot of money, we’d have a, you know, a $15 million plus plus recyclable fund that we could be recycling through projects all the time to get them off the ground, get them to the public financing phase, and then recycle that through to the next project in the next project. So that’s where that’s where we’d like to be in five years.

28:59

It sounds awesome. I look forward to watching the journey. So if people want to find out more, what how can people learn more about the calcia? In your work?

29:08

Yeah, they can visit the calci.org. And there’s a lot of different ways to get involved, whether you know, locally, if you want to sort of be a friend of the Kelsey in a community where we’re developing housing, getting involved in some of our advocacy and more will be coming analysis related to this federal stuff. And obviously, always, I would be remiss to say that we are always looking for generous philanthropic partners at all levels, whether it’s monthly givers in our community or, you know, multi year givers that are you know, funding our housing projects. So we’ve we’ve got, we’ve got an opportunity for everybody to make a contribution and get

29:40

involved. Wonderful. Thank you so much for being with me today.

29:43

Thank you. Thanks for having me and for spreading this this important work that we’re doing at the Chelsea but also in the field overall. So So thanks for including us in that.

29:55

I hope today’s discussion was valuable for you. If you like the show Don’t forget to subscribe to the podcast so you don’t miss an episode posted on social media, invite friends, and let me know if you have any suggestions for future topics. While you’re there, I’d be so grateful if you leave me a review. Your feedback will help me to improve the show. Do you have a question about the show? email me directly at Stephen at Steven beard dotnet. You can also check us out on Facebook by searching accessible housing matters or by visiting our website at accessible housing matters calm and all this can be found in our show notes. Join us next week for another great conversation about why accessible housing matters. Thanks for listening