People often use the term “ADA housing” or “ADA unit” when they are referring to one of two things: homes designed with accessibility features and/or homes where people with disabilities live.

The accessibility features in housing are multifaceted and governed by multiple laws and codes, with the ADA playing a small part, if any. In some cases, a person with a disability may live in a housing unit because of eligibility through a public program. Disabled people’s right to choose where they live is protected by multiple laws, including—but not limited to—the ADA.

To classify housing as “ADA” is inaccurate and oversimplified. Equating all accessible housing and housing reserved for disabled people with the ADA creates confusion and minimizes the diverse needs and rights of disabled people.

Instead, it’s important to understand which laws impact housing access and inclusion, and how the ADA shapes disability-forward housing.

The Problem with “ADA Housing”

Calling housing “ADA housing” or “ADA units” is misleading and ineffective for many reasons, including:

- It suggests the ADA alone governs housing accessibility, when in reality, many key protections come from the Fair Housing Act, Section 504, and/or other state and local building codes.

- It risks reinforcing the idea that disabled people should live in separate or specialized housing rather than having the freedom to live in the community like everyone else.

- It insinuates that because the law exists, things are covered, which is false. It also absolves the owners and operators of their responsibility to further implement the ADA and other key protections.

- It equates disability access solely with compliance– a check-the-box legal requirement– which is crucial but, on its own, limits only related disability as a site of compliance and fear of getting sued. Such a constrictive understanding of access limits what’s possible for residents and the building management.

- It also risks minimizing the diverse access needs of disabled people. Accessibility isn’t one-size-fits-all.

How the ADA Impacts Housing

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 is a vital civil rights law, but it only directly applies to housing in very specific situations. For example, the ADA imposes requirements for state and local government entities, regardless of whether they receive federal funding. Most of the time, housers will use the 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design, which include requirements that 5% of units are built for mobility access and 2% for communication access.

Title II of the ADA requires publicly funded (state, local, and federal) programs, including housing programs, to uphold community integration for people with disabilities. It protects disabled people from being forced into segregated settings when they can live in integrated housing with support. This rule was codified by the 1999 Lois Curtis v. Olmstead Supreme Court decision.

Even though the ADA only covers housing in specific situations, the ADA provides equal access to the internet and public spaces, essential to someone’s ability to apply to and live in housing and the surrounding neighborhood.

Moreover, the ADA sets requirements for public spaces, like common areas, which would apply to private multifamily housing, but nothing additional. Most accessibility requirements for private housing are established by other laws and local building codes.

Beyond the ADA: Fair Housing Act, Section 504, and Building Code

All laws vary in their scope, enforcement mechanisms, and applicability depending on the funding source, building type, and jurisdiction. With housing, far more of the legal protections for disabled people come from the following:

- The Fair Housing Act (FHA) of 1968 makes it illegal to discriminate in housing based on disability. It requires landlords and housing providers to allow reasonable modifications and accommodations for people with disabilities. The FHA also sets most private housing accessibility requirements.

- Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 applies to any housing that receives federal financial assistance. 504 requires the highest standards for access. It prohibits disability discrimination and requires accessible design and program access in federally funded housing.

- State and local codes are additional requirements adopted through building codes, accessibility standards (like ICC A117.1), or zoning incentives.

The Solution: Be Informed and Advance Disability-Forward Housing

Housers need to move beyond these generic and misapplied terms. Instead, housers can get specific about the accessibility features of particular units, engage inclusive design experts with and without disabilities early and often, and design and operate housing beyond just compliance.

It is essential to differentiate between the multiple components of creating accessible and inclusive housing for people with disabilities. The components are distinct and can overlap, but they don’t always. These include:

- In-unit and building design: Understand and comply with the legal frameworks and implement cross-disability inclusive design features that go beyond what’s required.

- Protection against discrimination: Ensure that all disabled people have equal access to the built environment and to all programmatic elements, like the application, leasing, or occupancy processes.

- Unit matching and targeting to particular access or service needs: If funding prescribes, market, lease up, and support target resident populations to live in units that are reserved for or prioritized (e.g., HUD Section 811 program). Regardless of funding, units can be identified by the particular accessibility needs that they meet (e.g., mobility, communication, vision, adaptable), and they can be matched with residents who have those particular needs.

- Access to services and supports: Design the building and operations strategies to support disabled people who need home and community based services.

By embedding these components, housers can advance disability-forward housing, which is inclusive, accessible, and affordable to disabled and non disabled people — built and operated under all relevant laws, and that goes beyond minimum requirements — that allows disabled people to live where and how they choose. Disability-forward housing can be understood and advanced across all corners of the housing field and during every step of housing development and operations. A first step can be checking out the Inclusive Design Standards.

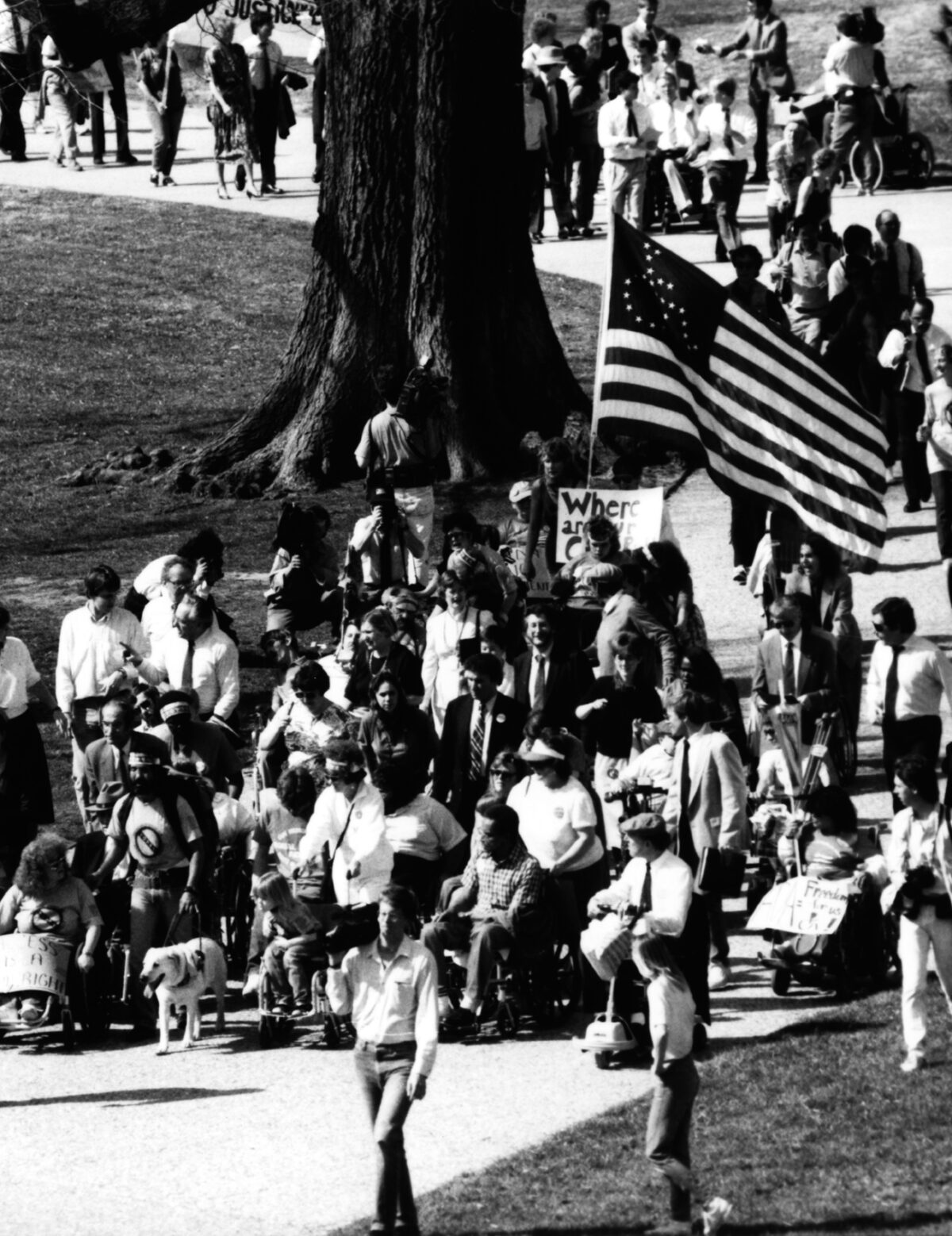

Housers aim to create the best housing products and experiences for residents. Yes, understanding and upholding the ADA and other legal protections is essential, but it is just one piece of the puzzle. This 35th Anniversary of the ADA, housers cannot just comply but take on the opportunity of disability-forward housing. Housers can be bold by including and centering the needs of disabled people because it truly creates better housing for all.

Want to learn more about disability-forward housing this 35th Anniversary of the ADA? Explore the following resources.

- Are you a houser?

- Are you a designer?

- Are you a government employee?

- Are you an advocate for disability-forward housing?

Want a deeper understanding of the legal requirements for people with disabilities in housing? Check out: