Sometimes, when people talk about creating communities, they talk about integration and inclusion as though they’re the same thing. While we favor as many community homes to be built for people with disabilities and people of all incomes as possible, we specifically focus on how communities can be truly inclusive. Our community stakeholders have echoed the same, wanting homes thoughtfully created with a sense of community and a value of diversity. Here we talk about ways to think about what to think through when creating truly inclusive communities.

Inclusion vs Integration

Education with students for disabilities, while not perfect, has advanced farther in respect to inclusion than housing and adult services and programs. Policies like Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) have required consideration of how to support student learning in the most inclusive setting while recognizing that that setting may look different for different students. The increasing focus on having all teachers certified in special education points to efforts to ensure all teachers serve and support students with disabilities, not just a select few. Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) have brought students with disabilities and their families together with educators and therapists to define the programs that serve that specific child best and evolve over time as the students do. There are applications from inclusive education that can and should be applied to our approaches in disability-inclusive housing.

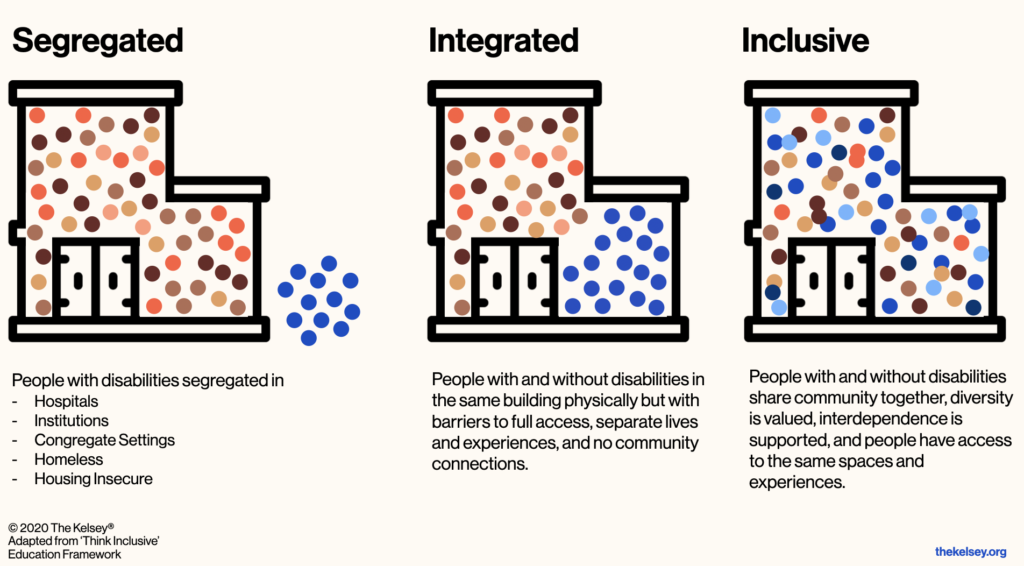

Education frameworks and approaches can also help us consider the differences between segregation, integration, and inclusion. In 2012, Think Inclusive shared a graphic depicting images showing the differences between exclusion, segregation, integration, and inclusion with simple dots and circles. We thought a similar tool could be created for disability housing, with our own graphic. For simplicity, we showed large apartment buildings, but these principles could be applied to many different housing types.

On the left, we see segregation, an unfortunate reality still today. People with disabilities are forced to live in isolated settings, only provided with housing options that segregate them from non-disabled individuals. Others, particularly with more medical needs or behavior supports, are relegated to hospital and institutional settings. Rather than design and fund programs that ensure people can receive the services they need in the community, our systems force people to live where those services are available and alongside people with similar needs. This segregated approach is a continued relic of decades of medical model approaches to disability and is directly in opposition to the principles of ADA and Olmsted. Finally, many individuals with disabilities experience homelessness. It’s estimated that 40% of the population experiencing homelessness has a disability. This is driven by a combination of factors including housing affordability, direct discrimination, and lack of appropriate supportive services.

Integration is where many of our approaches today in disability housing, and housing broadly, tend to land. As we’ve worked to build more community-based housing opportunities for people with disabilities, sometimes we only go so far as integrating that physical housing into other physical housing. This means housing is physically in the same place, but the community is not truly inclusive. We hear from some individuals with disabilities that although they live in the community, they don’t feel connected to their neighbors—they don’t have shared experiences or relationships with those around them; they experience loneliness, isolation, and even experience bias or discrimination. We know that people without disabilities experience these same feelings in their housing—there is a universal yearning for more inclusive and connected communities.

Approaches in integrated housing for people with disabilities sometimes also classify all people with disabilities as the same, treating the diverse community of people with disabilities as “one community.” This thinking favors approaches where we “stick” all people with disabilities in the same housing type or service program. Again, we achieve the goal of community-based housing in proximity and design but do so in a way that fails to recognize, accommodate, or support a diversity of individual needs in housing design, type of living setup, or service needs.

To the right, we see the ideal community of inclusive living—a truly inclusive community. While segregation and integration depicted people with disabilities as all the same orange dots, we now see a representation of different shades of orange. Truly inclusive models recognize the diversity within disability and the ways that diversity impacts what people desire in their housing and community.

In this inclusive depiction, we see people with disabilities fully mixed in a community with people without disabilities. We also note different clusters or groupings; inclusive housing approaches recognize and support that within a community people may group themselves in various ways. People with disabilities may choose to live with a roommate either with or without disabilities. Some may live in a shared living arrangement with staff or decide to live in a shared arrangement with others with disabilities. Some may live with a family member. Others may prefer to live alone. How and with whom people live varies and should be supported. It’s not easily shown in the graphic here, but a truly inclusive community also includes strategies to connect individuals, help neighbors feel valued and part of a community, and doesn’t splinter into segregated communities within the housing.

The goal of housing policy and programs should be inclusive models that mix housing for people of all abilities. Design and housing experiences should be the same quality for people, regardless of ability, and there should be thoughtful effort to create a true community for residents.

The most fully inclusive housing models recognize the diversity within disability, and the ways that diversity impacts what people desire in their housing and community.

Factors Impacting Inclusivity:

- The mix of tenants. Does the community include people of all abilities, incomes, and backgrounds?

- The recognition of diversity in disability. Does the community accommodate different types of disabilities and not require all living experiences to be the same?

- The connections between residents. Are services, culture, and ongoing programming done in a way that creates connection and builds a welcoming community?