Single-Stair Reform and People with Disabilities

Single-stair reform is gaining traction across the United States, with many cities and states considering its implementation. Advocates from across the nation are pushing to change building codes to allow taller buildings with a single staircase for egress (exiting the building), and some cities have already adopted changes to allow this. Single-stair reform has many benefits, including increased housing supply, lower construction costs, and more flexibility in apartment design. Additionally, paired with an increase in elevators, it would be an easy solution to create more accessible and disability-inclusive communities.

What are the Current Requirements for Apartment Buildings?

The International Building Code (IBC) is the predominant standard in the United States that establishes minimum building requirements for safety, structural integrity, and more. It requires residential buildings above three stories to have at least two staircases accessible for egress. Many argue this regulation is antiquated, originally stemming from the 1860s, with the purpose of increasing fire safety outcomes. It was put into effect before additional fire safety measures, like sprinkler systems and fireproof building materials, were created and implemented. The US is one of the few countries requiring two sets of stairs in residential buildings over three stories but actually trails behind many peer countries in fire safety outcomes.

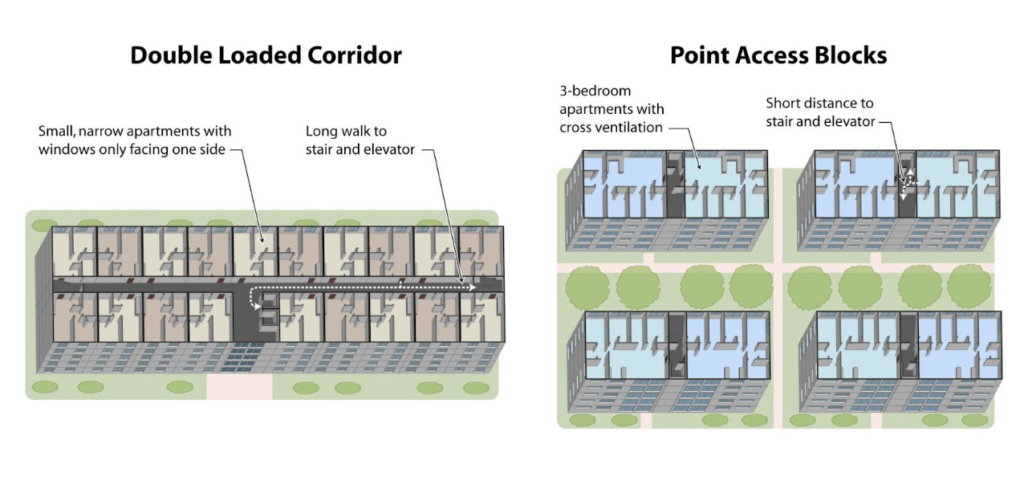

The two-stair requirement not only limits the size and floorplan (layout of the unit) options for multifamily units, it also increases construction costs. Because of this requirement, most multifamily buildings in the US have a hotel-like double-loaded corridor design, meaning a hallway with unit entries on both sides, which is extremely common in the US, but uncommon in other high-income countries. Many European countries contain apartment buildings consisting of no more than four units per floor with a single, centralized stair and elevator for egress – this is called a point access block.

Image Courtesy of Alfred Twu

What are Point Access Blocks?

Point access blocks can be up to six stories tall (in North America) and are more efficient than typical multifamily buildings because less space is dedicated to circulation (the pathways of movement within a building), giving more area to the actual units. This allows for larger rooms, better circulation within the unit, better physical access to windows, more room for storage, fixtures, and furniture, and more options to design for increased turning radiuses and wider hallways, all of which create more access for people with disabilities. Additionally, more efficient floor plates lead to less embodied carbon (greenhouse gas emissions) and a lower overall construction cost.

In point access blocks, units typically have at least two sides with windows, providing more daylight and allowing for cross ventilation and better temperature control. Conversely, double-loaded corridor designs only allow one side of a unit to have windows unless it’s a corner unit. Increased access to daylight has been proven to benefit mental health, and better ventilation in the home can improve air quality, prevent things like mold and mildew from growing, and reduce allergies and respiratory issues.

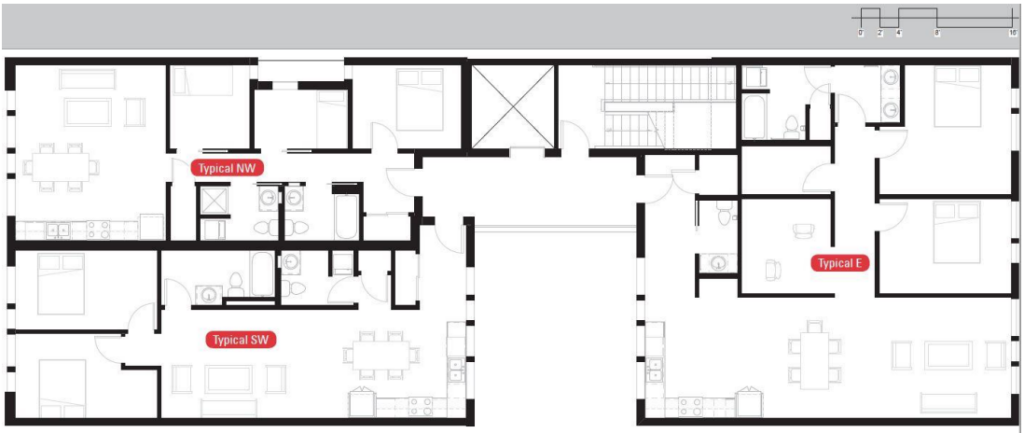

Third Floor Plan, image courtesy of schemata workshop

Point access blocks are an excellent option for achieving gentle density. Gentle density is the process of increasing housing options in existing neighborhoods by adding thoughtfully designed buildings to the existing available land, typically smaller lots. In the US, these housing options tend to be smaller or space-saving buildings like townhouses, which are not typically accessible. Point access blocks’ inherently efficient design allows them to be built on smaller lots nestled into existing communities. Their more flexible design options mean more 3- and 4-bedroom units can be built in neighborhoods, increasing housing possibilities for families. A better mix of unit types means downsizing or aging within the same building and community is easier. Additionally, single-stair buildings often foster a stronger sense of community by encouraging more interaction among residents in shared spaces.

By allowing smaller apartment buildings of up to five stories of purely residential or six stories of residential/mixed-use (five over one), up to 20 homes and even some amenities could be built on a single lot. These buildings can fit comfortably into neighborhoods and serve as a middle ground between single-family housing and high-rise apartment towers without dramatically changing the urban landscape.

Capital Hill Urban Cohousing, Seattle; photo: William Wright Photography, courtesy of schemata workshop

How Could Single Staircase Design Add More Accessibility to Housing?

Some critics of single-stair reform believe point access blocks inhibit accessibility by not having alternative means of egress and having minimized communal circulation spaces. These concerns are understandable but can be overcome by ensuring apartment buildings include elevators compliant with accessibility standards, fire suppression systems, like smoke detectors and sprinklers, smoke ventilation, areas of refuge (safe locations for people to gather) so people with mobility limitations can wait safely for assistance, and clear evacuation plans. Additionally, smaller circulation spaces mean less travel distance to reach one’s unit or an exit. Ensuring proper turn radiuses in the design can eliminate the concern around less communal circulation space.

When an elevator is provided in a residential building, all units must be Type B units, which means they can be adapted to be accessible. This results in more accessible units for people with mobility disabilities. As previously mentioned, the more efficient floor plates inherent in point access blocks allow more room to design for accessibility, and lower construction costs mean even the more costly accessibility features can be more easily implemented.

Single-stair reform can increase the supply of accessible housing, especially in urban areas, increasing the likelihood that people with disabilities can live in the neighborhoods they desire. Being closer to public transportation, medical care, grocery stores, places of employment, and other resources allows people with disabilities to live independently.

Current Progress on Single Staircase Reform

Several cities in the US, such as Seattle, New York, Honolulu, and Knoxville, have already legalized point access blocks, leading the way to more affordable, accessible housing. Seattle was the first city to legalize single-stair apartment buildings above three stories back in 1977. The Seattle Building Code has specific requirements that keep these types of buildings fire-safe, including (but not limited to) requiring sprinklers, a maximum of four dwelling units per floor, and a maximum travel distance of 125 feet to an exit. These cities are leading the way for other jurisdictions to update their local building codes.

In 2024, Tennessee legislators approved bills permitting local jurisdictions to allow (but not mandate) single-stair apartment buildings up to six stories; Washington State is set to allow the same by 2026. Virginia, Rhode Island, and New York State have all approved bills requiring the review of local building codes with recommendations to allow single-stair apartment buildings. And California approved a bill requiring fire officials to research and provide a report regarding standards of single-stair buildings above three stories. These efforts will help move the US toward fully legalizing point access blocks. The Center for Building in North America has a great online tracker allowing users to track single-stair reform in the United States and Canada.

Summary

Single-stair reform is a way to balance housing demand, affordability, and urban density while maintaining safety through modern construction standards. It promotes more affordable and efficient housing development by reducing construction costs and maximizing usable space. People with disabilities and the needs of disabled communities must be considered and prioritized when cities and states propose, pass, and implement single-stair reform. Disability-forward housing advocates can push to include single-stair reform in state and local policy agendas. They can connect and collaborate with other single-stair reformers to highlight this critical intersection. By enabling more flexible and cost-effective designs, single-stair reform helps address housing shortages, supports environmental sustainability, and provides opportunities for more inclusive and diverse housing solutions.